There’s a project underway in work called single sign-on and identity and access management. I’m not involved in it directly, although by its nature it touches on several things that I am working on at the moment. The goal, as the name implies, is to rid ourselves entirely of multiple sets of credentials: anything we use should have the same login ID and password, whether it’s one of our hosted systems (which, to be fair, already behave this way for the most part) or a third-party system like the webapp that we use to deliver training.

Since I’m not directly working on it this project is not really anything more than a blip on my radar, but it’s interesting to me because I’m attempting to do a similar thing at home, albeit on an entirely different scale to the large enterprise-wide project that’s I hear about in my professional life.

After the recent upgrade to my home server that I’ve blogged about before I now have several virtual servers included in our home network setup. One of these runs Windows Server 2008 R2, and I’ve made that one a domain controller that all the other computers (and servers) connect to. There are several benefits to this approach, but chief amongst them is a single set of credentials – I use the same username and password regardless of which of our home computers I’m logging on to, and when I change my password I change it once for it to be effective everywhere.

There are few web services running on our home network which require signing into, such as a web interface for centralized torrent downloads, a file browser, and a simple content management system that pulls everything together into an intranet of sorts. Most of these are PHP-based, and I’m on a mission to add SSO capability to these too.

I’ve discovered two main methods of enabling SSO in PHP that I’ll write about after the break, and my eventual plan is to tie the two methods together into a single cohesive sign-on module that I can reuse. Read on to find out what I’m up to!

LDAP (Lightweight Directory Access Protocol) Authentication

Wikipedia defines LDAP as an open, vendor-neutral, industry standard application protocol for accessing and maintaining distributed directory information services over an Internet Protocol (IP) network.

That’s a lot of fancy words for saying that LDAP provides an address book (think of the global address listing you see in Outlook, and you’re thinking of an LDAP database). PHP has a set of LDAP extensions that can be used to query the address book and retrieve user information, but in the context of authentication, we don’t even need to worry about any of that. An LDAP server can (depending on the implementation) be queried anonymously, or we can pass in some credentials with the query to get more detailed information back (again, depending on the implementation).

It’s this last part that’s important. Active Directory on a Windows domain controller is an LDAP server. In PHP, all we have to do is attempt to log on to the LDAP server. If we’re successful, it’s because the username and password that we input is valid on the domain. Even better, “valid on the domain” in this case means it’s an active account, the password is not locked, and all other account-level restrictions (such as a restricted set of logon hours) are considered.

All of this makes using LDAP to test the authenticity of a set of supplied credentials pretty trivial:

<?php

$username = "testuser"

$password = "pa55w0rd";

$domain = "testdomain.local";

$domaincontroller = "dc1.testdomain.local";

$ldap = ldap_connect($domaincontroller);

if ($bind = ldap_bind($ldap, $username."@".$domain, $password)) {

// user login successful

} else {

// user login failed

}

?>

That’s all there is to it!

Depending on what you had in mind when you read “SSO” in the title of this post though, we may not have met your requirements here. If we meant that the user has a single set of credentials then, fantastic – they do! But if our intention was to only require that a user enters their single set of credentials once (when they log on to Windows) then we’ve fallen short here. The code above requires the username and plaintext password, so we’d have to present some kind of web-based login form to the user to request that information and get all this to work.

Enter NT LAN Manager (NTLM) Authentication

If a website (or intranet site) is part of the intranet or trusted zones (found in the Internet Settings control panel applet) then that site is allowed to pass a header requesting NTLM authentication. When it does, windows passes a header back containing some information about the currently logged-in user without the user being prompted for their credentials in any way.

I obtained some simple example code from someone called loune at Siphon9.net and modified so that it doesn’t require apache as the webserver. Here’s the PHP:

<?php

if (!isset($_SERVER['HTTP_AUTHORIZATION'])){

header('HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized');

header('WWW-Authenticate: NTLM');

exit;

}

$auth = $_SERVER['HTTP_AUTHORIZATION'];

if (substr($auth,0,5) == 'NTLM ') {

$msg = base64_decode(substr($auth, 5));

if (substr($msg, 0, 8) != "NTLMSSPx00")

die('error header not recognised');

if ($msg[8] == "x01") {

$msg2 = "NTLMSSPx00x02x00x00x00".

"x00x00x00x00". // target name len/alloc

"x00x00x00x00". // target name offset

"x01x02x81x00". // flags

"x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00". // challenge

"x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00". // context

"x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00"; // target info len/alloc/offset

header('HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized')

header('WWW-Authenticate: NTLM '.trim(base64_encode($msg2)));

exit;

}

else if ($msg[8] == "x03") {

function get_msg_str($msg, $start, $unicode = true) {

$len = (ord($msg[$start+1]) * 256) + ord($msg[$start]);

$off = (ord($msg[$start+5]) * 256) + ord($msg[$start+4]);

if ($unicode

return str_replace("", '', substr($msg, $off, $len));

else

return substr($msg, $off, $len);

}

$ntlm_user = get_msg_str($msg, 36);

$ntlm_domain = get_msg_str($msg, 28);

$ntlm_workstation = get_msg_str($msg, 44);

}

}

echo "You are $ntlm_user from $ntlm_domain/$ntlm_workstation";

?>

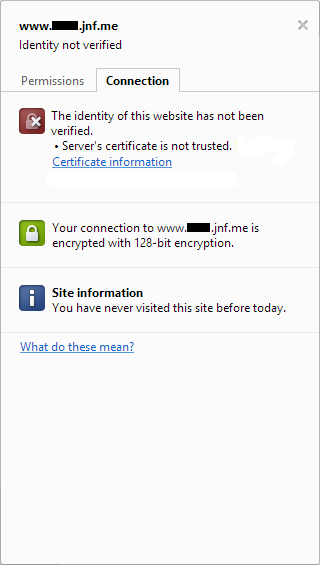

There’s a big problem with this code, and the problem is that it’s just decoding the user information from the HTTP header, and assuming that all is good – there’s no work done to confirm that the header is genuine, and there is a possibility that it could have been faked. We could do some tricks like confirming that the page request is coming from within our local network, but that doesn’t really solve the problem – HTTP headers can be manually defined by an attacker that knows what they’re doing, and what we’re doing here is a bit like asking for a username and then just trusting that the user is who they say they are without doing any further authentication.

Combining the Two Approaches

Included in the NTLM authorization header that gets sent to the webserver during the passwordless authentication interaction described above is an MD4 hash of the user’s password. A newer version of loune’s code retrieves this and confirms its validity using samba. Unfortunately that setup won’t work for me – my intranet webserver is running a customized version of samba that comes with the software I use to manage the linux computers that are attached to my domain, and this trick just flat-out fails.

However, if I have a plaintext version of the user’s password then I can use PHP to generate an MD4 hash of it for the purposes of comparison. So here’s my plan:

Scenario A: The first time a user comes to my webapp we’ll get their credentials using NTLM, including the MD4 hash of their password. Since we won’t know if this hash is valid, we’ll present the user with a screen asking them to confirm their password (but not their username). When they input it, we’ll confirm that their username and password combo is good using LDAP, and also generate an MD4 hash of the plaintext password that they entered to compare with what NTLM gave us. If nothing weird is going on everything should match. At this point we’ll store the MD4 password hash for future.

Scenario B: When a user returns to our webapp we’ll get their credentials using NTLM as before, and compare the hash NTLM gave us to our stored hash from their previous visit. If they match, we’re good, and there’s no need to ask the user to enter their password.

Scenario C: If the NTLM hash and the stored hash don’t match then the most likely scenario is that the user has changed their Windows password since their previous visit to our webapp. In that case we’ll throw out the stored hash and start again at Scenario A.

If anyone knows of a better approach (is there a centrify Kerberos tool that I could use to get an MD4 hash of the user’s password for the purposes of my comparison, for example?) then please let me know! I’d love to be able to achieve true passwordless SSO, but so far I can’t a method for doing so unless I switch my webserver from linux to Windows, and I don’t want to do that.