When I put my website together back whenever it was that I did that, I knew I wanted to get analytics from it: at the beginning the site was fairly simple (this blog, for example, was an entirely separate entity back then and it wasn’t integrated into the site in the way it is today), but from the start I wanted to know how many visitors I was getting, where they were in the world, how they were finding me, and a little about how they were interacting with my site.

I’d used Google Analytics on past projects, but this time around I felt a little uneasy about providing Google with an easy way to gather data on all my site visitors. Those guys have enough power without me contributing. I went with clicky.com for my analytics, and all was well.

In researching this post I found an article called Seven Reasons Why You Should NOT Use Google Analytics. My concerns about giving Google too much power rank number four in their list, but they ultimately reach the same conclusion I did – Google’s product offering in this space is simply better than the alternatives out there, especially when you consider the price (free). With Clicky the basic service is free but limited – you need to fork over some cash if your site generates a lot of traffic, or you want to retain data for longer than 31 days, or add advanced features… the list goes on.

I switched back to Google’s service a couple of weeks ago and I haven’t looked back. While I was at it I not only added the relevant code to this site, I also added it to Flo’s blog and the jnf.me landing page. Clicky limited me to tracking a single site but Google doesn’t, so why not?

For a website like mine adding the relevant JavaScript to the site and then forgetting about it is a reasonable approach, but I’ve discovered very quickly that if you’re prepared to put in a little more effort then you can get much improved results. For me, this was highlighted by the extremely limited usefulness of the data I’ve been getting from JNF.me, but the way I’m solving that problem could apply anywhere. Read on!

The Problem

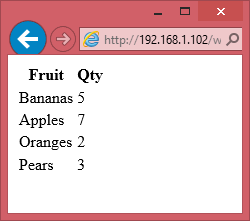

When I bought the domain jnf.me my primary concern was getting something short. My plan all along was to use sub-domains for the various bits of content that lived under it (www.jason.jnf.me, www.asiancwgrl.jnf.me, and so on). The J stands for Jason, the F for Flo, and the N for ‘n, but that’s not really relevant. Since it is the root of my domain, I knew I should put something there so I created a quick, fairly simple, single-page site. The page is divided into two with me on the left and Flo on the right, and if you click one of our faces then the whole thing slides over to reveal a little about us and some links to our online content.

In terms of analytics data, the very fact that this is a single-page site is what’s causing issues. With a larger like jason.jnf.me even taking the most basic approach to installing Google Analytics tells me, for example, that the average visitor views three pages. I know which pages are the most popular, which blog topics generate the most interest, and so on.

With JNF.me I know that people visit the page and then their next action is to leave again – but of course it is, there is only that one page.

What are they doing while they’re there? Are they leaving through one of the links on the page? I have no idea, but I can find out.

Manually Sending Pageviews

The first thing I opted to do was manually send a pageview to Google Analytics when somebody clicks one of our pictures to slide out the relevant content from the side of the page.

My rationale for this approach is that if this were a site with a more traditional design, clicking a link to view more content from the site would indeed cause another page to be loaded. The fact that my fancy design results in the content sliding in from the side instead really makes no difference.

The approach is extremely simple, and adding a single line of JavaScript to the code that makes the content slide in is all it took:

ga('send', 'pageview', {'page': '/' + p });

So how does this work? ga() is a function that Google Analytics creates when it’s first loaded by the page, and in fact if you’re using Google Analytics at all then you’re already using this. Let’s take a quick look at the code Google has you paste into your page in order to start feeding data to Analytics in the first place. It ends with these two lines:

ga('create', 'UA-XXXXXXXX-X', 'auto');

ga('send', 'pageview');

The first line initializes things and lets Google know (via the UA-XXXXXXXX-X bit) which Analytics account it’s going to be getting data for. The second line sends a pageview to Analytics because, well, if the code is being executed then that means somebody is viewing the page.

By default Analytics makes the perfectly reasonable assumption that the page that executes this code is the one it should be recording a pageview for, but here’s the thing: it doesn’t have be that way.

Back to my example, and you’ll notice I’ve added a third argument to the ga() function call. Google’s help page on the subject discusses the options in terms of possible parameters, but essentially what I’m doing is passing a JavaScript object that describes exactly what Analytics should track. The page field is the page address against which a pageview is registered, and the p variable is used elsewhere in my code that makes the sliding content work: it stands for person, and it contains either “jason” or “flo” as appropriate.

The important thing to note here is that these pages don’t exist – there is nothing on my website at either /jason or /flo – but this doesn’t matter. Analytics registers a pageview for one of these addresses anyway, and I know when I see it in my data that it means that somebody opened the sliding content.

Sending Events

In addition to sending pageviews to Analytics you can also send events, and this is the approach I took to help me understand how people are leaving the page.

When I first started learning about events I spent some time trying to understand the right way to use them. Google’s Event Tracking help page provides an example, and you can find some good reading material about it on the web. The conclusion I’ve reached from my brief research is that there is no “right” way to use events – you just define them in whatever way works best for you, your site, and your desired outcome.

The important thing to know is that events have, as a minimum, an associated category and action. You can also optionally define a label and a value.

I can see that the value parameter would be extremely useful in some scenarios, such as tracking e-commerce sales (you could, for example, use Analytics to track which traffic sources result in the highest sales figures in this way) but I don’t need that. I will be using the other three parameters, though.

When you view data regarding events in the Analytics interface, they’re in something of a hierarchical structure. Categories are treated separately from one another, but you can view summary data at the category level, then drill-down to segment that data by action, then drill down further to segment by label.

For the events fired when a site visitor clicks an external link on my page I arbitrarily decided that the category would be ‘extlink,’ the action would be the person the link relates to (either jason or flo), and the label would be indicative of the link destination itself (blog, twitter, etc).

To implement this, the first thing I did was add a class and a custom data attribute to the links on the page:

<a href="http://twitter.com/JayWll" class="outbound" data-track="jason/twitter">Twitter</a>

The class of outbound defines this as an outbound link as opposed to one of the links that helps visitors navigate around the page, slide content in and out, etc, and the data-track attribute defines what will become the event’s action and label.

Next, the JavaScript. This time around it’s slightly more in-depth than the single line of code we used to send a pageview. That’s not necessarily a function of events as compared to pageviews, but it’s due to the nature of what I’m tracking here: when a user clicks a link that takes them away from the current page, they (by default) leave immediately. In order to track outbound links, I actually need to hold them up and make sure the event is registered with Analytics before I let them go anywhere. Happily, Google has thought of that and the ga() function accepts a hitCallback property. This is a function that’s fired only once the event has been properly recorded.

Here’s my code:

$('a.outbound').click(function(e) {

e.preventDefault();

trURL = $(this).attr('data-track');

nvURL = $(this).attr('href');

ga('send', 'event', {

'eventCategory': 'extlink',

'eventAction': trURL.split('/')[0],

'eventLabel': trURL.split('/')[1],

'nonInteraction': 1,

'hitCallback': function() {

location.href = nvURL;

}

});

});

The first thing I do is prevent the link’s default behaviour with the line

e.preventDefault();

Next, I capture the link’s data-track and href attributes – we’ll need both of those later.

Finally, we’re back to the ga() function to send data to Analytics. We send an event, and define its parameters within the JavaScript object: the category is ‘extlink,’ the action and label are obtained by splitting the link’s data-track attribute, we define this as a non-interaction event (LMGTFY) and, once this data has been successfully sent, the hitCallback function is executed which takes us to the page specified by the link’s href attribute.

Easy, when you know how.

Taking it Further

The possibilities here are endless, and how use them really depends on your site and the data you’d like to get from it. My plan is to take some of what I’ve learned for jnf.me and extend it to this site, particularly in regards to event tracking.

In addition to tracking outbound links, I have two other ideas for how I might use this:

- Page length and scroll tracking

Some of my posts – this one is potentially a prime example – are pretty long. I do tend to ramble on a bit at times. If a post is more than, say, two screen heights in length then I could track how many people scroll beyond the halfway point and how many people scroll to the end to help me understand if my audience is OK with long posts or if I should split in-depth content into some kind of mini-series.

- Form tracking

There’s a contact me page on this site, and each post in this blog has a comment form at the bottom. With events I could gain a much better understanding of how these are working and how visitors interact with these forms. For example, do people begin filling out the contact me form but then abandon it at some point before submitting? Do people begin to write comments on my posts but then refrain from posting it when they find out I require them to at least provide their email address?

Hopefully you have ideas for how you can use these techniques to provide better insight into visitor behaviour on your site too. Come back here and leave a comment to let me know how it goes! I do require your email address for that, but I promise not to spam you or pass it on to any third party.