Recently, for reasons I’m sure I’ll write about in the

future, I needed to find a way to use JavaScript to test if either of two

web-locations are accessible – my home intranet (which would mean the user is on

my network), or the corporate intranet of the company for which I work (which

would mean the user is on my organization’s network). The page doing this test

is on the public web.

My solution for doing this test was simple. Since neither

resource is accessible publicly I put a small JavaScript file on each, then I

use AJAX and jQuery to try and fetch it. If

that’s successful, I know the user has access to whichever intranet site served

the request and my page can react accordingly.

If neither request is successful I don’t have to do

anything, but the user doesn’t see any errors unless they choose to take a look

in the browser console.

This all worked wonderfully until I enabled SSL on the page

that needs to run these tests, then it immediately fell apart.

Both requests fail, because a page served over HTTPS is

blocked from asynchronously fetching content over an insecure connection. Which

makes sense, but really throws a spanner into the works for me: neither my home

nor corporate intranet sites are available outside the confines of their safe

networks, so neither support HTTPS.

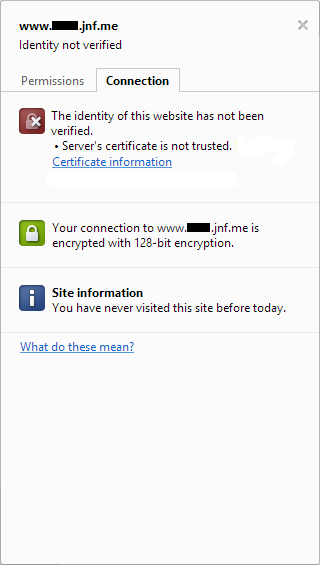

My first attempt at getting around this was to simply change

the URL prefix for each from http:// to https:// and see what happened. Neither

site supports that protocol, but is the error that comes back different for a

site which exists but can’t respond, vs. a site which doesn’t exist? It appears

so!

Sadly, my joy at having solved the problem was extremely

short lived. The browser can tell the difference and reports as much in the

console, but JavaScript doesn’t have access to the error reported in the

console. As far as my code was concerned, both scenario was still identical

with a HTTP response code of 0 and the status description worryingly generic “error.”

We are getting closer to the solution I landed on, however.

The next thing I tried was specifying the port in the URL. I used the https://

prefix to avoid the “mixed content” error, but appended :80 after the hostname

to specify a port that the server was actually listening on.

This was what I was looking for. Neither server is capable

of responding to a HTTPS request on port 80, but the server that doesn’t exist

immediately returns an error (with a status code of 0 and the generic “error”

as the descriptive text), but the server that is accessible simply doesn’t

respond. Eventually the request times out with a status code of 0 but a status

description, crucially, of “timeout.”

From that, I built my imperfect but somewhat workable

solution. I fire a request off to each address, both of which are going to

fail. One fails immediately which indicates the server doesn’t exist, and the

other times-out (which I can check for in my JavaScript), indicating that the

server exists and I can react accordingly.

It’s not a perfect solution. I set the timeout limit in my

code to five seconds, which means a “successful” result can’t possibly come

back in less time than that. I’d like to reduce that time, but when I

originally had it set at 2.5 seconds I was occasionally getting a

false-positive on my corporate network caused by, y’know, an actual timeout

from a request that took longer than that to return in an error state.

Nevertheless if you have a use-case like mine and you need

to test whether a server exists from the client perspective (i.e. the response

from doing the check server-side is irrelevant), I know of no other way. As for

me, I’m still on the lookout for a more elegant design. I’m next going to try

and figure out a reliable way to identify if the user is connected to my home

or corporate network based on their IP address. That way I can do a quick

server-side check and return an immediate result.

It’s good to have this to fall back on, though, and for now

at least it appears to be working.